Introduction

Beacon Object Files (BOFs) have revolutionized the way we execute code in memory on Windows systems, particularly within the Cobalt Strike framework. As you may know, I have been working on my own C2 framework, emp3r0r, which aims to bring similar capabilities to Linux environments. In this post, I will share my journey of adapting the BOF workflow for Linux, the challenges faced, and the solutions implemented.

The source code for the Linux BOF loader can be found at linux-bof-loader.

Wait, Why Not memfd_create + ELF?

It's shameful that you are even asking this question.

In Linux, everything is a file. memfd_create sounds like it runs your code in memory, and you need much fewer code to do it. However, read it aloud: fd means a FILE. Your smartass "fileless" technique is not even fileless! The kernel creates a pseudo-file in /proc/<pid>/fd/ that points to your memory region. A simple cat can dump your entire payload. And you almost certainly have to call execve on that file descriptor to run it, which is NO BETTER than just running it from disk.

memfd_create is noisy and heavily monitored by EDRs. But you might argue that MAP_ANONYMOUS is also monitored. True, but mmap leaves no file descriptor or pseudo-file behind. It's just a memory region in your process which is normal behavior for any Linux process.

If you worry about MAP_ANONYMOUS being detected, consider using module stomping techniques to hide your BOF code by overwriting memory regions of some legitimate loaded shared library you mmapped.

Understanding BOFs: Why Object Files?

BOF files are essentially object files that are compiled from C source code. In the build process, these files are the intermediate step before linking them into a final executable. Unlike traditional executables, object files are standalone pieces of code that can be linked dynamically.

Why go through the trouble of loading .o files instead of just dropping an ELF binary or a shared library (.so)?

- Stealth & Memory Forensics: Executing a standard ELF binary often involves

execve,memfd_create, which guarantees that your malware will light up like a Christmas tree. Loading a shared library still leaves behind traces in/proc/<pid>/maps. In contrast, loading an object file directly into memory usingmmapand executing it leaves minimal footprints, making it much harder to detect through memory forensics. - Size: A full ELF executable carries a lot of baggage (segments, headers, padding). A relocatable object file contains only the code and data we wrote. It's tiny, making it perfect for network transmission over C2 channels.

- Position Independence: Object files are designed to be linked. They don't assume a fixed base address, which makes writing a custom loader that

mmaps them anywhere in memory much more natural than fighting with an ELF executable's preferred load address.

The Challenge: Relocations on Linux

Porting this concept to Linux wasn't as simple as recompiling a Windows loader. Windows uses the COFF format; Linux uses ELF. While the concepts are similar, the implementation details are worlds apart.

The biggest hurdle was implementing the dynamic linker logic in user space. When you compile code with gcc -c, the compiler leaves "holes" in the machine code wherever you reference a global variable or an external function. It then creates a .rela.text section telling the linker how to fill those holes.

In my loader, I had to implement handlers for the x86-64 relocation types commonly generated by GCC:

R_X86_64_64: Absolute 64-bit addresses.R_X86_64_PC32: 32-bit offsets relative to the Program Counter (RIP). This is the standard for function calls.R_X86_64_PLT32: Usually used for calls to shared libraries.

The tricky part is that standard Linux binaries use a Global Offset Table (GOT) and Procedure Linkage Table (PLT) to handle external calls lazily. For this loader, I didn't want that complexity. Instead, I implemented "eager binding": when the loader sees a relocation for printf, it finds the address of printf in the host process immediately and patches the code to jump directly to it. This bypasses the need for constructing a complex GOT/PLT structure in memory.

// Apply Relocations

for (int i = 0; i < ehdr->e_shnum; i++) {

if (shdrs[i].sh_type != SHT_RELA)

continue; // We only support RELA (x86-64 standard)

// The section inside our memory we are modifying

uint32_t target_sec_idx = shdrs[i].sh_info;

if (sec_offsets[target_sec_idx] == 0 &&

(shdrs[target_sec_idx].sh_flags & SHF_ALLOC) == 0) {

continue; // Relocation for a section we didn't load (e.g. debug info)

}

uintptr_t target_base_offset = sec_offsets[target_sec_idx];

int num_rels = shdrs[i].sh_size / sizeof(Elf64_Rela);

Elf64_Rela *rels = (Elf64_Rela *)(obj_buf + shdrs[i].sh_offset);

for (int r = 0; r < num_rels; r++) {

Elf64_Rela rel = rels[r];

uint32_t sym_idx = ELF64_R_SYM(rel.r_info);

uint32_t type = ELF64_R_TYPE(rel.r_info);

// Where to write the patch (Address in our process)

uintptr_t patch_addr =

(uintptr_t)mem_base + target_base_offset + rel.r_offset;

// Resolve Symbol Address

Elf64_Sym sym = symtab[sym_idx];

uintptr_t sym_addr = 0;

if (sym.st_shndx == SHN_UNDEF) {

// External Symbol (e.g., printf)

const char *name = strtab + sym.st_name;

// RTLD_DEFAULT finds symbols in the global scope (libc, etc.)

void *handle = dlsym(RTLD_DEFAULT, name);

if (!handle) {

fprintf(stderr, "Unresolved symbol: %s\n", name);

return -1;

}

sym_addr = (uintptr_t)handle;

} else if (sym.st_shndx == SHN_ABS) {

sym_addr = sym.st_value;

} else {

// Internal Symbol (defined in this object)

sym_addr =

(uintptr_t)mem_base + sec_offsets[sym.st_shndx] + sym.st_value;

}

// Perform Calculation based on type

switch (type) {

case R_X86_64_64: // *p = S + A

*(uint64_t *)patch_addr = sym_addr + rel.r_addend;

break;

case R_X86_64_32: // *p = (uint32)(S + A)

*(uint32_t *)patch_addr = (uint32_t)(sym_addr + rel.r_addend);

break;

case R_X86_64_32S: // *p = (int32)(S + A)

*(int32_t *)patch_addr = (int32_t)(sym_addr + rel.r_addend);

break;

case R_X86_64_PC32: // *p = S + A - P

case R_X86_64_PLT32: // Treated same as PC32 here (direct binding)

{

int64_t val = (int64_t)sym_addr + rel.r_addend - (int64_t)patch_addr;

*(uint32_t *)patch_addr = (uint32_t)val;

break;

}

default:

fprintf(stderr, "Unsupported relocation type: %d\n", type);

return -1;

}

}

}

The Argument Problem

The second major challenge was: How do we get data into the BOF?

In a standard C program, main gets argc and argv. But a BOF isn't a program; it's just a function entry point. I wanted to maintain compatibility with the "Beacon API" style used in Cobalt Strike, where arguments are packed into a single binary buffer.

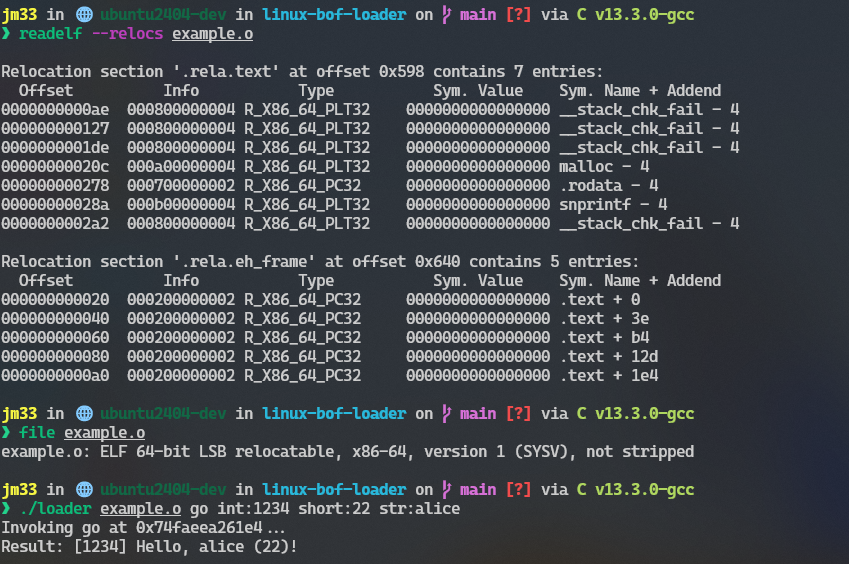

This protocol is simple but strict: a 4-byte length prefix followed by the data. The problem is that C is terrible at dynamic types. To solve this, I wrote a CLI packer in the loader that takes typed arguments from the command line:

./loader example.o go int:1337 str:"Hello World" short:25

The loader parses these prefixes (int:, str:, bin:), serializes them into a contiguous byte buffer, and calculates the total payload size. It then passes a pointer to this buffer as the first argument to the BOF's entry function.

On the BOF side, I implemented a header-only library that mimics the Cobalt Strike parsing API (BeaconDataInt, BeaconDataExtract, etc.). This allows the payload to "unpack" its arguments safely without knowing the memory layout of the host loader.

// Parses "type:value" strings

Buffer *pack_args(int argc, char **argv) {

Buffer *b = malloc(sizeof(Buffer));

b->buf = malloc(128);

b->size = 0;

b->capacity = 128;

// Total size header placeholder (will fill at end)

buf_write_int(b, 0);

for (int i = 0; i < argc; i++) {

char *arg = argv[i];

char *val = strchr(arg, ':');

if (!val) {

fprintf(stderr, "Error: Arg '%s' missing type prefix (e.g. int:10)\n",

arg);

return NULL;

}

*val = 0; // Split string

val++; // Point to value

if (strcmp(arg, "int") == 0) {

buf_write_int(b, atoi(val));

} else if (strcmp(arg, "short") == 0) {

buf_write_short(b, (short)atoi(val));

} else if (strcmp(arg, "str") == 0) {

buf_write_str(b, val);

} else if (strcmp(arg, "bin") == 0) {

buf_write_binary(b, val);

} else {

fprintf(stderr, "Unknown type: %s\n", arg);

return NULL;

}

}

// Write final total size (excluding the 4-byte header itself) to index 0

int total_payload_size = b->size - 4;

memcpy(b->buf, &total_payload_size, 4);

return b;

}

An example BOF using this API looks like:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <string.h>

// The parsing context

typedef struct {

char *buffer; // Current pointer

int length; // Remaining length

} datap;

// Initialize the parser

// We skip the first 4 bytes (total size header) to match standard tooling

static inline void BeaconDataParse(datap *parser, char *buffer, int size) {

if (!parser || !buffer)

return;

parser->buffer = buffer + 4;

parser->length = size - 4;

}

// Extract a 4-byte Integer

static inline int BeaconDataInt(datap *parser) {

if (parser->length < 4)

return 0;

int32_t val;

memcpy(&val, parser->buffer, 4);

parser->buffer += 4;

parser->length -= 4;

return (int)val;

}

// Extract a 2-byte Short

static inline short BeaconDataShort(datap *parser) {

if (parser->length < 2)

return 0;

int16_t val;

memcpy(&val, parser->buffer, 2);

parser->buffer += 2;

parser->length -= 2;

return (short)val;

}

// Extract a Binary Blob (or String)

// Returns a pointer to the data in the buffer.

static inline char *BeaconDataExtract(datap *parser, int *size) {

if (parser->length < 4)

return NULL;

uint32_t len;

memcpy(&len, parser->buffer, 4);

parser->buffer += 4;

char *out = parser->buffer;

parser->buffer += len;

parser->length -= (4 + len);

if (size)

*size = (int)len;

return out;

}

char *go(char *args, int size) {

char *buffer = malloc(128);

datap parser;

BeaconDataParse(&parser, args, size);

// Order matters! Must match how you packed them.

int id = BeaconDataInt(&parser);

short age = BeaconDataShort(&parser);

char *name = BeaconDataExtract(&parser, NULL); // Reads string

snprintf(buffer, 128, "[%d] Hello, %s (%d)!", id, name, age);

return buffer;

}

Dealing with Symbols

Finally, a BOF is useless if it can't interact with the OS. It needs to call socket, open, write, etc.

Since the object file doesn't link against libc at compile time, the loader must act as the bridge. I utilized dlsym(RTLD_DEFAULT, name) to perform runtime symbol resolution. When the loader encounters an undefined symbol in the ELF symbol table (marked SHN_UNDEF), it queries the host process's address space.

This creates a powerful capability: the BOF can call any function available to the loader process, including internal functions if we choose to expose them.

if (sym.st_shndx == SHN_UNDEF) {

// External Symbol (e.g., printf)

const char *name = strtab + sym.st_name;

// RTLD_DEFAULT finds symbols in the global scope (libc, etc.)

void *handle = dlsym(RTLD_DEFAULT, name);

if (!handle) {

fprintf(stderr, "Unresolved symbol: %s\n", name);

return -1;

}

sym_addr = (uintptr_t)handle;

} else if (sym.st_shndx == SHN_ABS) {

sym_addr = sym.st_value;

} else {

// Internal Symbol (defined in this object)

sym_addr =

(uintptr_t)mem_base + sec_offsets[sym.st_shndx] + sym.st_value;

}

Comments

comments powered by Disqus